www.caselaw.site

An appeal to the High Court has been filed in Schaeffner v Tasman District Council. TDC alleges mobile homes are minor dwellings.

We argue chattel housing is not realty, and if not realty, not structure, not building, not dwelling hence not minor dwelling. It is an argument well settled in common law but not considered in NZ courts. This web site serves as a case reference file.

DOWNLOAD: NZEnvC 180.pdf

DOWNLOAD: MHA analysis

DOWNLOAD: MHA Brief

Next Step: Appeal has been filed. We need to help raise funds for the Schaeffners to hire lawyers. This is a test case to knock back bad cases in Beachen and Schaeffner.

Caselaw

- Elitestone[1997] or Download in Word Format

- Chelsea [2000]

- Savoye [2014]

- Skerritts [2000]

- Salmond Jurisprudence [1902]

Briefs

- Analysis of Beachen v Auckland Council

- Draft: Friend of the Court filing

- Brief: Mobile Home – chattel or realty?

- Afflixing Objects to Land – Losing title to Objects

NZ Cases

Common law cases relevant to mobile homes

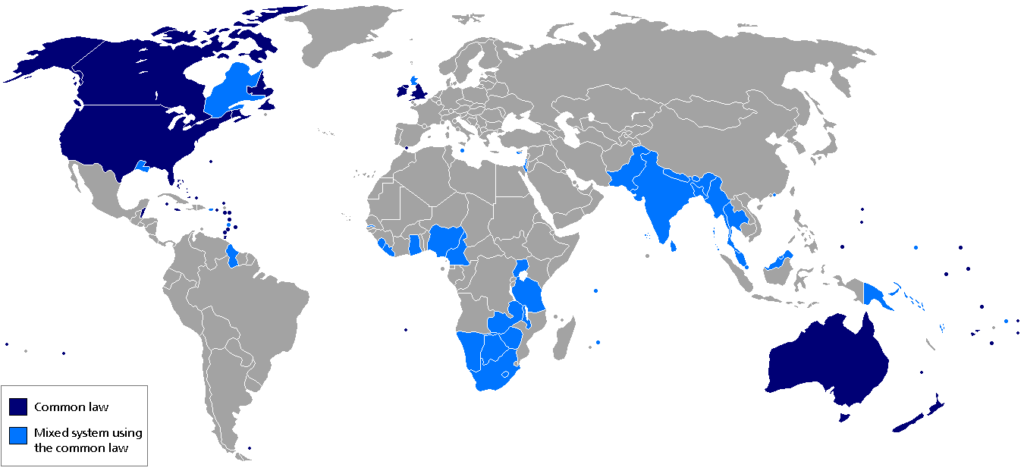

While some judges prefer domestic cases to precedent established overseas, Elitestone v Morris [1997] is the case citied by the NZ Environment Court judge in Beachen v Auckland Council [2023]. Unfortunately David Beachen did not retain a lawyer. The Council and judge cited Elitestone to bolster their arguments, but failed to cite any of the extensive case law that refuted their arguments. Had Beachen retained a lawyer who had read Elitestone, the Council would have had no case. This is important because in subsequent abatement orders, Council cites Beachen.

Elitestone says:

“If a structure can only be enjoyed in situ, and is such that it cannot be removed in whole or in sections to another site, there is at least a strong inference that the purpose of placing the structure on the original site was that it should form part of the realty at that site, and therefore cease to be a chattel.”

and

“A house which is constructed in such a way so as to be removable, whether as a unit, or in sections, may well remain a chattel, even though it is connected temporarily to mains services such as water and electricity. But a house which is constructed in such a way that it cannot be removed at all, save by destruction, cannot have been intended to remain as a chattel. It must have been intended to form part of the realty.”

This is not a technical loophole. It goes to the heart of law, but also offers a solution to the severe affordable housing crisis that is polarising NZ. Because they are not fixed to land and do not commit the land like buildings do, mobile homes can be here today / gone tomorrow, leaving only bare soil. They cost under $100,000, are made in factories in two weeks and are installed onsite in two hours. But before they can be used, it must be shown they are not minor dwellings under the Unitary Plan.

Relevant questions

- How is the unit connected to the land?

- How does the unit connect to utilities?

- Is the unit landlocked? (typically if made on site)

- Did the unit come on site intact?

- Is the unit able to be removed intact?

- Does removal require taking apart or demo?

- Is it under 4.3m height including transporter?

- What is required to relocate it off the land?

- Does the unit add to the land value?

- Is the unit listed on the land record as a fixture?

- Is the unit subject to rates?

- Is the unit covered by homeowners insurance?

- Is the unit financed as part of the mortgage?

- Can the bank claim it in mortgage default?

Irrelevant questions:

- Is the unit permanently occupied by people?

- Unattached decks adjacent to the unit?

- Unattached sheds (unless they landlock)?

- Is the unit attached to utilities?

- Does it have a heat pump?

- Does it have a kitchen?

- Does it have a bathroom?

- Is the unit on blocks or stands held by gravity?

- If a trailer, are the tyres removed?

- If a trailer, is the draw bar removed?

- If a trailer, has the light-bar been removed?

- Is the trailer registered or has a current WOF?

The question is it a vehicle is irrelevant to the question chattel or realty, meaning if it is not a vehicle, that is not proof it is realty. However, if it is a vehicle, then clearly it cannot be realty. This tends to be the opposite of how cases are argued in NZ.

What should be used instead?:

While the law is deficient and the Council’s solution undermines RMA s5, s18A and in some cases s36AAA(3)(a) , simply securing a court decision that declares mobile homes as chattel housing, thus excluding from rules on minor dwellings, is not good government. Reasonable, affordable and rapid evaluation and approval for appropriate sites should be in place.

Covenant on Title: One of the legal tools in the Planning Department’s tool kit when seeking to control an activity is to agree with the land owner to place a 15-year covenant on title that sets out the agreement. This mechanism is very flexible, because it is site specific.

The cost to file a covenant on title is $90. The covenant itself should be a standard form, not a negotiation between council and landowner lawyers. It should begin with an application, similar to a dog license that shows what, where, how many and how it fits with waste water, site coverage, setback, parking and other rules. It should not however consider rules on minor dwellings, because mobile homes are not part of the land. When the need passes they can be removed intact without difficulty. They also have a much more effective resolution to nuisance activity, such as noise or trash… unlike a minor dwelling which must be demolished (won’t happen), Council can order the mobile home’s removal: tow it away.

The checklist would be reviewed by the duty officer, and if no barriers encountered, the consent should be signed and filed wit LINZ. In lieu of lost rates, it is proposed the applicant pay initial fee of $90 to file the covenant and the first year rates equivalent of $200 should be collected. All approved units should have GPS transmitters and a central government office should manage the map. It would collect a $220 annual fee of which $200 goes to the council and $20 to manage the record. All should be automated.

Question of Law: Mobile Home… realty or chattel?

Realty = Minor Dwelling > Dwelling > Building > Structure > Fixed to Land > Land

In Beachen v Auckland Council [2023], the judge wrote in [18] “…, to be a “minor dwelling” the tiny home must be a “dwelling”. To be a dwelling it must, among others, be a “building” and to be a building it must be a “structure”. The decision failed to make the final link in the chain: To be a structure it must be realty.

Property Law: Realty is real property / real estate as opposed to chattel (personal property). In Jurisprudence [1902] §155. Movable and Immovable Property, NZ’s most eminent jurist, Sir John Salmond, former NZ Solicitor General and Supreme Court Judge, set out the distinction between land and chattel:

Among material things the most important distinction is that between movables and immovables, or to use terms more familiar in English law, between chattels and land. In all legal systems these two classes of objects are to some extent governed by different rules, though in no system is the difference so great as in our own …

Dividing Line: Case law in the UK focuses on the dividing line between things which are fixed and not fixed. (Horwich v Symond [1915] 84 LJKB 1083] & Savoye and Savoye Ltd v Spicers Ltd. [2014] EWHC). As is often the case, the question is not binary but a continuum, thus the finder of fact must test the facts against the established law, to find if the facts cross the line from chattel to realty. This is well-established law that seems to have been overlooked in recent NZ cases.

NZ Distraction: In contrast, case law in New Zealand focuses on a subsidiary question is it a vehicle, because the only appeals court case to address the question is Te Puru a Building Act 2004 case focused on s8(1)(b)(iii) (building includes a a vehicle… that is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent or long-term basis. This has become a distraction, obscuring the central question.

Re-focus: The purpose of the upcoming test case expected to be Davis v Auckland Council is to refocus the question on whether mobile homes not fixed to land are minor dwellings, hence structures under the RMA. The case cited by the Council is its own Beachen v Auckland Council [2023] which failed to address the question adequately (see Analysis of Beachen v Auckland Council). In Beachen, the judge cited Elitestone but did not address its central question of chattel/realty.

Current Status of the Test Case

UPDATE: It appears Auckland Council has decided to not issue an abatement order to Davis. Thus, our attention is shifting to TDC where the question is now before the High Court on Appeal. This page will be updated when time allows.

As of 16 February 2024, an abatement order had been issued (and then apparently revoked) against S Davis alleging Davis had three unconsented minor dwellings on his property in the form of mobile homes owned by third parties who paid Davis ground rent to park their mobile homes on his land. The order was revoked because it was issued in November 2023 calling for the mobile homes to be removed by April 2023 [sic] and because the order was issued without following the internal approval process of Auckland Council.

A new inspection occured on 7 March 2024 where Davis asked the inspectors to pay especial attention to the meaning of fixed to land, and to ensure the Council does not lose the expected appeal to the Environment Court on a technicality as happened in Antoun v Hutt City Council [2020] where the judge found the Council’s abatement order was fatally flawed, even though the evidence in that case pointed to Jono Voss’ fabrication being a structure, not a vehicle.

Subsequent to the inspection, several Building Act Notices to Fix (NTF) and an abatement order was issued, but not on the allegation of minor dwellings. The abatement order addressed the way one of the tenants was handling grey water, which Davis reports has been fixed. The NTF’s were equally minor and are being sorted.

But there may be another case/

However, on 23 April 2024, Stuff ran an article on a very similar case where Beth Collings has been issued an abatement order on her tiny home. As with Davis, it requires she either obtain a resource consent or “disestablish” the tiny home. This same, somewhat odd word, disestablish, was used in Davis’s first abatement order, suggesting it was not the quirk of an officer, but a carefully selected word. One would expect in common English to be told either to obtain a resource consent or move the tiny home off the land. However, while admitting nothing, it is possible Council is selecting disestablish because if they said move it, it would clearly show it is a moveable, hence under common law, chattel not realty. And if not realty, it’s not a minor dwelling, thus the order is ultra vires.

In Collings case, it has been estimated the cost for a consent will be $40,000, of which half is a developer contribution. How is a person wanting to park a mobile home on someone else’s land a developer? The idea of developer contributions was for developers… businesses that buy land with a greenfield zoning (usually rural) which becomes far more valuable as soon as it is rezoned for development and subdivided into lots. The developer gets a windfall while the ratepayers have to fund the capitalisation of road widening and new pipes. In rezoning, the council does see a commensurate increase in its rates, thus the ongoing costs are funded by ongoing new rates, but there is a reasonable argument the council ratepayers should not be subsidising the developer.

Somehow, the Council has engaged in administrative creep to now capture Beth Collings.

As with Davis, the Council cites Beachen [2023] as the basis of its allegation of minor dwelling.

Appeal of Abatement Order or Declaration?

The Davis case was expected to be an appeal of an abatement order, but either Council is holding off until the advocate returned from overseas (a courtesy requested by Davis), or Council has decided Davis is prepared to overturn the basis of their issuing abatement orders and is choosing to duck the case. With the new Collings order, there is an opportunity to move the case to her.

The alternative is to ask for a declaration on the meaning of minor dwelling in the context of chattel housing. This would extend beyond mobile homes (such as Chelsea [2000] where target was a houseboat), covering homes made in factories that are delivered intact by truck, placed on blocks, not fixed to land.

To be clear, Council can amend the Unitary/District Plan to embrace mobile homes, but amending becomes a political matter. The problem is not the RMA or Building Act, it is the way Council is using them as revenue collecting instruments. S18A requires the Council to use timely, efficient, consistent, and cost-effective processes that are proportionate to the functions or powers being performed or exercised. $40,000 is not efficient or cost effective and certainly not proportionate to an $80,000 mobile home.

As a political matter, while we argue a technical matter of law, politicians cannot deny there is a serious affordable housing crisis doing considerable damage to the social fabric of New Zealand. A win forces them to address the core issue. Fault clearly lies with government policy. Mobile homes are an immediate, interim solution where government is part of the problem, not part of the solution.